It was in 1889 that Lilla Cabot Perry first encountered Claude Monet’s work at the prestigious Galerie Georges Petit in Paris which staged a Monet/Rodin collaboration exhibition (Claude Monet-Auguste Rodin, centenaire de l’exposition de 1889), that opened on June 21st. It was also in that summer of 1889 that Lilla and her husband first met the great French painter. According to an article written by Lilla, which appeared in the March 1927 edition of the American Magazine of Art, a young American sculptor who was living in Paris mentioned to her and her husband that he had a letter of introduction to meet Monet but he was very nervous and shy with going on his own to the great man’s house so asked the couple if they would accompany him on his visit. Lilla and Thomas Perry were delighted to accept the invitation as they had greatly appreciated what they had seen at the Claude Monet-Auguste Rodin exhibition.

In the article Lilla recounts her first impressions of Monet. She wrote:

“… The man himself with his rugged honesty, his disarming frankness, his warm and sensitive nature, was fully as impressive as his pictures and from this first visit dates a friendship which led us to spend ten summers at Giverny. For some seasons, indeed, we had the house and garden next to his and he would sometimes stroll in and smoke his afternoon-luncheon cigarette in our garden before beginning on his afternoon work…”

The Impressionism style that Lilla encountered with the art of Monet was an epiphany moment for her. She immediately took to this style even though it was still rejected and scorned by the art world around her. The way the Impressionists managed the colour and light was a great inspiration to her and during those summer days at Giverny she also worked with many American artists, who had found their way to the small French town to sample the joys of plein air painting in the rural surroundings, such as Theodore Robinson, John Breck, and Theodore Earl Butler.

One of her painting during her time in Giverny was her 1889 work entitled La petite Angèle II. It is impressionistic in style with its free form brushstrokes that capture the impression of light and colour. Claude Monet, inspired Perry to work en plein air, and use impressionistic brushstrokes, soft colours, and poppy red. If you look through the window depicted in this work you should note the early stages of what would become Lilla’s love affair with the way the Impressionists treated landscape depictions.

A similar work by Lilla was entitled Angela. It was a portrait of one of her favourite models in Giverny. The clearly defined figure posed in a freely brushed and light-filled setting typifies academic American Impressionism of the time.

In late 1889 Lilla Cabot Perry and her husband left Giverny and embarked on a tour of Belgium and the Netherlands. In 1891 she returned to Boston with her family bringing home a painting by Monet and a number of landscapes works by John Breck. Once back in Boston she began to spread the word of Impressionism especially the works of Monet. However, like many art critics in France, Impressionism was not favoured by either the American critics or the buying public and Lilla had to begin with a hard-sell of his works. She would exhibit his works at her home and give talks about him and the world of Impressionism to the Boston Art Students’ Association.

Whether Bostonians accepted the merit of Monet’s work or not, the one thing for sure was that they appreciated the paintings of Lilla Cabot Perry, especially her portraiture. Several of her paintings were exhibited at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago and were greeted with great acclaim. In 1897 she exhibited work at the St Botolphs Club in Boston and the art critic of the Boston Evening Transcript wrote:

“…Mrs Perry is one of the most genuine, no-nonsense, natural painters that we known of………………Such work must be taken seriously…”

Lilla Perry’s artistic success in 1889 had made it possible for her to be one of the select few young artists to be admitted to Alfred Stevens’ class in Paris. The works of Lilla Perry were often influenced by the time she spent with Stevens. A good example of this is her 1893 painting entitled The Letter [Alice Perry] and the way she has depicted the chair, especially the careful attention she has paid to the colouration of the wood, and the way she has depicted her youngest daughter’s clothes in such detail. It is a loving portrait of a nine-year-old daughter by her mother.

In 1894, sheonce again exhibited her impressionism paintings at the St. Botolph Club in Boston together with other Impressionism artists, including Edmund Tarbell, Phillip Hale, Theodore Wendel, and the British-born painter Dawson-Watson. Three years later, and in the same gallery, Lilla held a solo exhibition. On show were her Impressionist-style portraits and landscapes.

This proved to be a major turning point for Lilla Perry as it showed that her work was gaining the recognition of the American art world and that Impressionism was finally being acknowledged as a legitimate artistic expression. Lilla Perry was a devoted Impressionist painter and she loved the work of the Impressionists, especially the works of her friend Claude Monet. Now back in America she took every opportunity to endorse French Impressionism and urged her friends to invest in their work. She also gave many lectures and wrote essays for journals and magazines supporting this French art movement.

Between 1868 and 1872, Lilla’s husband, Thomas Perry, was a tutor in German at Harvard and from 1877 to 1881, he was an English instructor in English as well as being a lecturer in English literature from 1881 to 1882. Thomas Perry was offered a new challenge in 1897 when he was presented with the opportunity to take up a teaching position in Japan as an English professor at the Keio Gijuku University in Tokyo. Lilla and her husband along with their three children left America and travelled to Japan. Not only was this and exciting time for her husband it was also a stimulating time for Lilla and offered her new opportunities to paint.

In 1898, he became professor of English literature in the Keio University, in Tokyo, Japan. The Perry family lived in Japan for three years and Lilla immersed herself in its artistic community. Lilla Perry met Okakura Kakuzō, one of the Imperial Art School co-founders and became an honorary member of the Nippon Bijutsu-In Art Association, an artistic organization in Japan dedicated to a Japanese style painting known as Nihonga.

Such an involvement in the Japanese art and Asian art in general helped Lilla develop her unique style which fused western and eastern artistic traditions.

The result of this coming together of east and west can be seen in her Impressionist portraits.

It was not just her portraiture that Lilla focused on during her three-year stay in Japan, she also completed a number of landscape works. By far her most favoured subjects were ones depicting Mount Fuji. Of about eighty paintings she completed whilst in Japan, thirty-five depicted the iconic mountain.

Lilla and her family left Japan for America in 1901 and settled back into their house in Boston. Her three daughters were now all in their twenties and their mother had completed a number of paintings feature all of them or as individuals. In an early painting entitled Open Air Concert, which she completed in 1890, she depicts her three daughters in a garden setting with her eldest, Margaret, with her back to us, posed playing the violin.

Almost ten years later Lilla’s three musically-talented daughters featured in her 1901 painting entitled The Trio, Tokyo, Japan (Alice, Edith and Margaret Perry). In 1903 Lilla and Thomas Perry bought a farm in Hancock, New Hampshire. She said she immediately fell in love with the area as it reminded her of Normandy, an area she knew well from her days at Giverny.

Alice Perry, Lilla’s youngest daughter featured in her mother’s portrait entitled Portrait of Mrs. Joseph Clark Grew [Alice Perry]. Joseph Grew married Alice Perry on October 7th, 1905 and became her husband’s life partner and helper as promotions in the diplomatic service took them around the world. The couple went on to have two daughters, Lilla Cabot in 1907 and Elizabeth Alice in 1912. Lilla’s portrait of her daughter won her a bronze medal at the prestigious International Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in St. Louis.

In the first decade of the twentieth century Lilla Cabot Perry divided her time between Boston and France but her health had started to deteriorate possibly due to all the travel she was doing but also because of financial problems. Her inheritance had dwindled and she was the main source of the family income through the sale of her paintings. The financial difficulties the family were experiencing meant that she had to spend a lot of her time completing portraiture commissions to make up for the money that her family was losing in investments. She once declared that she had had to complete thirteen portraits in thirteen weeks, four sitters a day at two hours each. It also rankled with her that she had to concentrate on portraiture as her Impressionistic landscapes were viewed as too experimental by her conservative patrons. An example of her portraiture work around this time was her 1912 Portrait of William Dean Howells, the prolific American novelist, playwright and literary critic.

In 1923 Lilla was struck down with diphtheria and at the same time she was struggling to support her middle daughter, Edith, who had suffered a mental breakdown and was admitted to a private mental health institution in Wellesley, Massachusetts. Lilla spent two years convalescing in Charleston, South Carolina.

Lilla Perry, like many other nineteenth century painters, was unhappy with the new avant-garde trends in Modern art such as Fauvism led by Henri Matisse and André Derain and so in 1914 she, along with Edmund Tarbell, William Paxton and Frank Benson, helped form the ultra-conservative Guild of Boston Artists in order to oppose the art world’s avant-garde trends. In 1920 Perry received a commemoration for giving six years of loyal service to the Guild.

During her time convalescing she discovered a new inventiveness for her landscape works, what she termed as “snowscapes.” These beautiful winter landscapes laden with snow became a craving 0f Lilla’s and she would go to extreme lengths to capture winter scenes en plein air, even bundling herself up in blankets and hot water bottles in order to capture the beauty of a 4 a.m. sunrise. One of her most famous “snowscapes” was her 1926 work entitled A Snowy Monday.

Her summer home in Hancock soon became her main residence and she and her husband Thomas settled into village life in the picturesque New Hampshire foothills. Thomas Perry died of pneumonia on May 7th 1928, aged 83. Lilla Cabot Perry continued to paint prolifically until her death on February 28th, 1933. Lilla and Thomas Perrys’ ashes are buried at Pine Ridge Cemetery in Hancock.

Enter Paul Durand-Ruel who was to play a part in Alfred Sisley’s life in the 1870’s. Durand-Ruel was born in Paris, on October 31st, 1831, the son of shopkeepers Jean Durand and Marie Ruel. It was in their shop that they allowed famous artists to display their paintings and sketches. In the 1840’s, their shop soon became a regular rendezvous for artists and collectors alike, so much so that Jean Durand decided to turn their shop into an art gallery. Their seventeen-year-old son, Paul, joined the family business in 1848. It must have been an exciting time for the young man as he was sent all over Europe to seek out new artists and sell their paintings. In the mid-nineteenth century, his father’s gallery specialized in paintings produced by the landscape artists of the Barbizon School, such as Corot. Paul Durand-Ruel knowledge of art grew and in 1863 he was acknowledged as the firm’s resident art expert. Following the death of his father in 1865, Paul Durand-Ruel took over the business.

Enter Paul Durand-Ruel who was to play a part in Alfred Sisley’s life in the 1870’s. Durand-Ruel was born in Paris, on October 31st, 1831, the son of shopkeepers Jean Durand and Marie Ruel. It was in their shop that they allowed famous artists to display their paintings and sketches. In the 1840’s, their shop soon became a regular rendezvous for artists and collectors alike, so much so that Jean Durand decided to turn their shop into an art gallery. Their seventeen-year-old son, Paul, joined the family business in 1848. It must have been an exciting time for the young man as he was sent all over Europe to seek out new artists and sell their paintings. In the mid-nineteenth century, his father’s gallery specialized in paintings produced by the landscape artists of the Barbizon School, such as Corot. Paul Durand-Ruel knowledge of art grew and in 1863 he was acknowledged as the firm’s resident art expert. Following the death of his father in 1865, Paul Durand-Ruel took over the business.

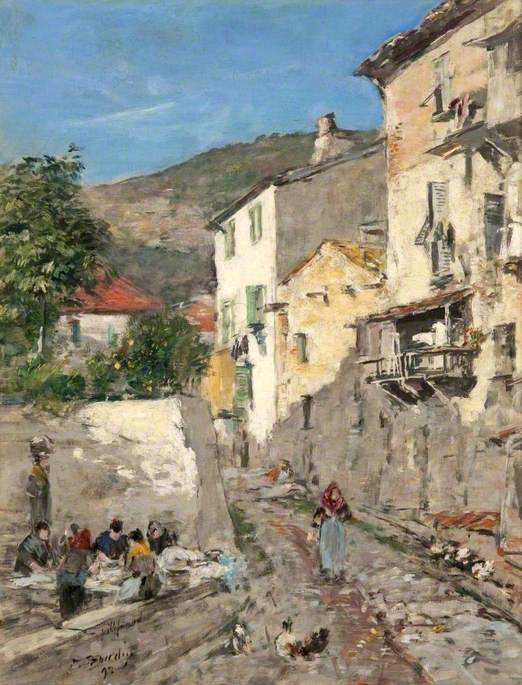

In July 1874, Sisley made a return trip to London with his friend the famous French Opéra-Comique singer, Jean-Baptiste Faure, an avid collector of Impressionist paintings. Faure bankrolled their trip by buying six of Sisley’s works. The pair stayed initially in South Kensington before moving to Hampton Court. Hampton Court was a popular leisure resort with good accessibility to central London. In that year Sisley completed a painting depicting part of the bridge joining Hampton Court with the small village of East Molesey on the south side of the river Thames. It was entitled Une Auberge à Hampton Court (Hampton Court Bridge: The Castle Inn). The Castle Inn, which some believe could have been where the pair were staying, is the focal point of the painting. The relaxed leisurely feeling is depicted by the elegantly clothed figure as he saunters down the road towards us. Sisley has overpainted the light grey ground with bright tones. Look how Sisley has emphasised the broad gravel street by placing his figures to the very edge of it and by doing this he has established a broad vacant zone directly in front of us.

In July 1874, Sisley made a return trip to London with his friend the famous French Opéra-Comique singer, Jean-Baptiste Faure, an avid collector of Impressionist paintings. Faure bankrolled their trip by buying six of Sisley’s works. The pair stayed initially in South Kensington before moving to Hampton Court. Hampton Court was a popular leisure resort with good accessibility to central London. In that year Sisley completed a painting depicting part of the bridge joining Hampton Court with the small village of East Molesey on the south side of the river Thames. It was entitled Une Auberge à Hampton Court (Hampton Court Bridge: The Castle Inn). The Castle Inn, which some believe could have been where the pair were staying, is the focal point of the painting. The relaxed leisurely feeling is depicted by the elegantly clothed figure as he saunters down the road towards us. Sisley has overpainted the light grey ground with bright tones. Look how Sisley has emphasised the broad gravel street by placing his figures to the very edge of it and by doing this he has established a broad vacant zone directly in front of us.